Costa Rica has been a country with almost no heroes. Despite the governing elites’ fervent attempts to invent them, exalt them, recycle them from the past, and feature the heroic deeds of remarkable men (and literally only men) in school textbooks as a way of mobilizing national sentiments, there have been no heroes capable of giving the entire population goosebumps of unifying national pride.

In the late 1980s, and quite unexpectedly, a national living hero fell from the heavens when we learned that a Costa Rican was flying into space with NASA. There was a mad rush to invite him to Costa Rica and do everything possible to lodge him in the hearts and minds of the nation. During a welcome event organized for him on a main street of the capital, school children and teachers received him and were able to see a real astronaut with their own eyes. Yet shortly thereafter, someone revealed a rather unpleasant detail: Franklin Chang had renounced his Costa Rican nationality years earlier, and was now a citizen of the United States. Re-nationalizing Chang thus became a priority. The last thing we needed was for a hero of such high caliber to turn out to be a gringo.

Here was a perfect opportunity to highlight his heroic qualities, which, of course, had all been acquired in our country. In April 1995, and for the first time in history, the Costa Rican state awarded honorary citizenship to a person born in Costa Rica. Since then, there has been no lack of news about him. We flew with Chang through outer space and we prayed to Negrita, our national Virgin, every time he needed a safe landing.

El Chino—as he is known, because like many Costa Ricans he is of Chinese descent—was ours. The fact that he was Chinese was in fact an advantage, as the boom of multiculturalism arriving from North America was teaching us to embrace diversity and ignore inequalities. For many, his magic faded when he took part in the Commission of Notables, which was responsible for revising and recommending the Free Trade Agreement with the United States. El Chino, though having fallen from heaven, turned out to be quite earthbound—after all, his own company’s headquarters were based at NASA, with a subsidiary in Costa Rica.

A much less-known fact is that Chang is not the only Costa Rican to have flown into space. In 2003, Elia Arce––another Costa Rican living in the U.S.––made her first voyage to the moon. She brought with her an old suitcase packed with objects associated with Costa Rican identity, which she sought to deconstruct.

Her performance First Woman on the Moon first took place in Los Angeles, though there were several other subsequent departures––including one from Cuba, only 90 miles from Cape Canaveral. And do not think for a second that the government rushed to call up this astronaut, to fill us with national pride over her journey, or to ask her to be an honorary citizen. The arts could not compete with the prestige of business, especially at a time when the former had not yet been rationalized in the neoliberal terms that they are today. Today, art must appeal to its own profitability and impact on the GDP in order to receive funding from the State.

Arce’s adventures in the performance world began twenty years before her landing on the moon. Her first piece––performed in 1990 shortly after the beginning of her voluntary exile in the U.S.–– reflected her experiences as an undocumented worker cleaning hotel rooms. It was called Make Up Room, Please Do Not Disturb and was presented during a stay at the Banff Centre for the Arts (Alberta, Canada).

Transart Foundation. Houton, Tx. Executive Producer: Surpik Angelini. Directed and edited by Lawrence Elbert.

Transart Foundation. Houton, Tx. Executive Producer: Surpik Angelini. Directed and edited by Lawrence Elbert.

Transart Foundation. Houton, Tx. Executive Producer: Surpik Angelini. Directed and edited by Lawrence Elbert.

She worked with the Banff Centre service staff on the piece, which consisted of acts of cleaning conducted in an almost choreographic manner and interwoven with personal histories of the workers, many of whom were immigrants with backgrounds in the arts. The last of Arce’s works in the U.S.––before her voluntary return to Costa Rica––was a group piece called Light Green, Dark Green, which was performed as part of the Project Row Houses in Houston. In this piece, various herbs were planted in an old shotgun house. The community would later take care of these herbs, using them to make green juices.

The result was a communal garden that neighbors could eat from, and where courses on organic farming could be taught. Between these two projects lies a search of almost thirty years that began when, upon emigrating, Arce watched with awe as others’ perceptions of her body transformed her into someone else.

For by entering the U.S., Arce unknowingly became part of a group of people who are racialized through their appearance and judged according to existing stereotypes and prejudices. These stereotypes are applied to whoever arrives; the latter are subsumed into homogenizing categories of “Latino” or “Hispanic”––categories that erase differences between immigrants from different parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. Shortly afterwards, when Arce became part of the art world, she was encouraged several times––in a gesture of solidarity––to assimilate into a group of people who did not want to assimilate into the dominant national culture.

Her artistic companions invited her to become Chicana. As the number of immigrants from Costa Rica is not very large, there was no specific idea in the U.S. about what it meant to be Costa Rican. Becoming Chicana, on the other hand, would be to adopt an identity that already had strong claims. But Arce preferred the difficulty of contemplating and explaining what it meant to be Costa Rican, rather than the ease of beginning a process of Chicanization. For this would have meant blurring herself in order to assume a borrowed identity and in doing so, would reinforce racial reductionism. As she found herself in this forcibly homogenizing space––presented with the offer to adopt a “ready-made” Chicana identity––Arce was faced with a problem. How could she explain to her theater and performance friends or her audiences that even if what they saw before them looked like a Hispanic, a Latina, an immigrant, and a Chicana, what she actually wanted to be was Costa Rican? This turned out to be difficult, for even she herself did not entirely know what this meant. From that moment on, she would search for and invent this identity incessantly through her performance pieces.

In Costa Rica, a country of mixed people, Arce was white, and that was that. Because the official identity narrative in our country is entirely centered on whiteness––despite the fact that reality contradicts this fantasy––and because Arce is from the Central Valley––the area around the capital––she had never before felt the need to ask questions about race. Then she arrived in a country marked by a permanent nostalgia for a white national identity––once invented and never true––and there, Arce became “of color.” This racialization, along with her efforts to be Costa Rican, sparked in her fundamental questions and a need to find out more about her ancestors. Fortunately, she discovered an indigenous grandmother, as would almost anyone who shakes her family tree in these lands. And so, Arce continued to search and assemble the parts that would lead to the explanation of a self still under construction. In this context, her body became the only territory where she was legal––where she could feel at home––but she first had to appropriate it. It was not until she embraced performance art as a method of subjectification––one through which she could disrupt the categories forced upon her––that she was able to dialogue with the imposed status of immigrant/Latina, and assume a new existence brought about by and through displacement.

The notion of “being Costa Rican,” still undefined and in the process of invention, was a creative springboard for Arce. It is quite possible, however, that in the eyes of many, she remained Chicana, Latina, Hispanic, brown, etc. But Arce stood atop these categories and practiced her chosen manner of existence. Being Costa Rican, during this time of asphyxiating identity politics, did not mean assuming the identities that were in fashion, but rather choosing to be a stranger under construction.

This was perhaps her way of demanding the right to be seen in her particularity, in her fight against assimilation. In this case, not only assimilation into the official culture, but also into any identity construct––such as Chicana identity––that is threatened by discourses of multiculturalism when it is accepted by the dominant group, thus becoming fashionable and being used to create an image of a country in which everyone supposedly has both a place and equal rights. For this reason, Arce instrumentalized her body. She offered it as a spectacle and turned it into an object of attraction/rejection. Marked by the dynamics of her voluntary exile, her body served as a way of setting into motion histories that were simultaneously hers and others’. From that moment on, she became a bearer of knowledge, and could not go from one place to another without displaying that knowledge. It was the memory of an embodied historical knowledge that demanded the triggering of processes of remembrance.

And so, her body––as a site for the coexistence of conflicting knowledges––absorbed the official U.S. discourse of multiculturalism in order to exceed it. Her body was her tool of confrontation, her way of speaking, a space of propositions, insofar as she used her body both to expose the expectations of a system and to express her desire not to become the stereotypical Latina needed in service of the “political efficacy” of U.S. multiculturalism. At some point, Arce acquired––within North American society––a micro-space that she decorated with parts of an identity that she had taken from her micro-country and demystified. For Arce, her particular way of being Costa Rican was politically necessary as an insertion strategy––to avoid assimilation into Chicana or Latina identity––even though she spoke only for herself and not for Costa Rica. She found this possibility through performance art. She needed to criticize racism, sexism, and discrimination, and she discovered that possibility in performance art.

She needed to question the supposed certainties learned from her family, the school system, and on the streets about what it meant to be Costa Rican. Performance art became that oracular space, that experimental laboratory for forms of existence more comfortable than those she had been forced to absorb. She appropriated the right, without anyone’s permission, to invent the contents and the meaning of both her identity and her icons, so that they could accompany her and so that she could destroy them. This implied a process of selection: the rescuing of certain pieces of her culture, some of which made it to the moon in her suitcase without her having packed them, some of which she collected during visits to Costa Rica.

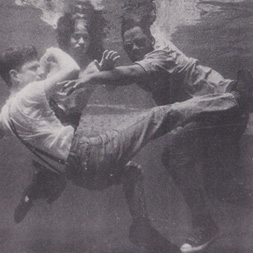

Thus, through the performance of her being––as a ritual of renovation––she has rewritten her own history. Since then, Arce, like many people living in physical and cultural transit, has proposed a symbolic exchange with her country of exile. This is an exchange nobody asked her for. Her country of origin rarely paid attention to it, and never responded. But she has not ceased to be reborn, just as she did, for example, in her performance Bathtube, in which she was born in a bathtub. For The Long Count, Elia built a cocoon on a wall, crawled into the cocoon to lead the life of a chrysalis, and was born a few hours later. Through this journey, she displayed her fears, disgusts, and desires so that no one would ever again inscribe an identity within reach of dominant institutions and symbols onto her body. So that no one would represent her. So that she could dismantle even subtle attempts to move her into constellations that she did not want to be a part of. So that she could at negotiate the meanings that she wanted, when she wanted them.

So radical was this process that, once she felt capable of doing so, she appropriated images from U.S. iconography in the performance Pin-up Girl. This was a way of facing the fear and anger she felt when the U.S. declared war on Iraq. Arce transformed herself into a pin-up girl, and through this image, corrupted the iconography of white U.S. American women—sexy, objectified, and used to feed the sexual fantasies of soldiers so that this vital energy could be invested into combat. Or, she became the immigrant Latina who, like many others, cleans someone else’s shit for a few dollars, as she did in her performance I Have So Many Stitches That Sometimes I Dream I’m Sick. But even after her long journey across the earth and to the moon, Costa Rica did not call up Arce to give her honorary citizenship, nor did it present her as a model example in schools. Children did not accompany their teachers to the main streets of the capital to welcome her. The motherland does not turn critical women like her into heroines. Nevertheless, she returned to Costa Rica. But before returning, she created one final performance as a regular inhabitant of a country that also did not claim her: she sowed, harvested, and then packed up her suitcase yet again, landing in our country.

This cuaderno does not include all that she has produced in Costa Rica since then. That task remains for the future––a book that will show what she has done now that she is back, with the help of that art form they call performance.