In Discipline and Punish (1975), Michel Foucault dedicates a brilliant chapter to “docile bodies,” which unveils how the form of power characteristic of the modern era has enclosed bodies through a series of mechanisms, including the restriction of space, the regulation of time, the serial decomposition of sequences in movements, and the configuration of functioning collectives. The French philosopher did not precisely address the manner in which this meticulous control of the body is specified according to individual attributes (such as age or gender) or collective ones (such as nation, class, or other social categories). Based on his keen observations, however, it is possible to infer that subaltern bodies (women, black people, workers, minors, etc.), marked as “abnormal,” have been more intensely submitted to regulation, vigilance, and punishment.[1]

Foucault’s findings, centered on prisons, hospitals, and other technologies of power, can be extended to the arts, specifically with regards to how the representation of the body in the visual arts has been codified in various epochs. In his book Corpus solus. Para un mapa del cuerpo en el arte contemporáneo, Spanish critic Juan Antonio Ramírez writes that the codification of the corporeal in western art has emerged from the tension of “two opposed poles that paradoxically constitute the fundamental components of its cultural heritage: the classic pagan and the Judeo-Christian tradition” (2003, 33; translated for this edition). Although the perfect/healthy body is the virtuous body in both cases, the classic pagan affirms the body, and celebrates “all the modalities of its representation,”[2] while Christianity––the other polarity––inherited the Jewish aniconism (the rejection of images), thus creating the tendency to view nudity as negative or sinful (33; translated for this edition).

From this perspective, we may regard contemporary art as the history of a progressive deconstruction of both canonical forms of corporeal representation. Neither measurable nor archetypal, the body is increasingly represented as a concrete reality that gradually brings to the surface everything that was repressed by “canonical” western culture. During the modern period, the first avant-gardes promoted a different treatment of the corporeal in images that drew from “primitivism” and “orientalism” of romantic origin, according to which nudity was a return to “the golden age”––that is, an invocation of paradise (Ramírez 2003, 36; translated for this edition).[3] Yet despite this work of the avant-gardes to create new ways of conceiving of nudity and its pictorial or sculptural representation (e.g. “immoral” poses that reveal the erotic) against the grain of Christian and neoclassical canons, a gendered division of labor persists. As the Guerrilla Girls brought to light through their enormous billboard hung near the Metropolitan Museum in New York City and emblazoned with the famous phrase “Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met?”, men continue to be the subjects (painters/sculptors) and women the objects (models) of representation, even in the modern era.

Contemporary art goes even further, mainly because it has set itself the task of demonstrating the return of the “real” as a method of historical revenge, of staging everything that first Christianity and then modern rationalism foreclosed from the social imaginary in general and the visual arts in particular. Thus, the deformed, the grotesque, the disgusting, the vulgar, and the monstrous––in short, everything that had been considered abject––have not only gradually displaced the “beautiful” as an aesthetic ideal, but have transformed the nature of the sublime, which loses its grandiose dimension to give way to what, for a long time, was considered unbearable, perturbing, and unworthy of being represented in images.[4]

This fight for the body and for the representation of the subaltern body has remained one of the fundamental topics of contemporary art. As North American artist Barbara Kruger once noted, the female body is “a battlefield.” Assuming this declaration as a working hypothesis, there are some fundamental questions that need to be addressed: How do we wage this battle for and on the body in contemporary art? Why are female artists the protagonists of this fight? What are the modalities and reach of the deconstruction of the patriarchal gaze, as well as its articulation in nationalism, imperialism, and Christianity? In what follows, I explore some answers to these questions with regard to a particular case: the deconstruction of Costa Rican national identity by performance artist Elia Arce.

Art, Body, and Nation in Costa Rica

For approximately fifteen years, the “nationalist imaginary” in Costa Rica has been under siege in contemporary art. The height of nationalist art in the last century took place between the 1930s and the 1950s, and found its greatest talents in artists like Teodorico Quirós and Fausto Pacheco. They constructed a representation of the nation based on a bucolic imaginary that idealized the local landscape and naturalized the social, as Eugenia Zabaleta (2003) convincingly demonstrates in La patria en el paisaje costarricense.

For a long time, the construction of “how we Costa Ricans are” occurred primarily through the notion of the border––that is, by differentiating Costa Ricans from non-Costa Ricans, from the external “others” in the imaginary.[5] In Costa Rica, the “other” has had two faces: the European (usually Swiss or Spanish) or North American on one side, and the Central American (epitomized by Nicaraguans) on the other. The first represents the “ideal of self”––the one with which the “official” Costa Rican identifies, given that he looks in the mirror and sees himself as one of them.[6] In this context, there is a tendency for the Central American to play the role of the “abject,” to represent everything we do not want to be, everything that is denied, rejected, and foreclosed.

The “post-nationalist art” that has rather shyly forged its path over the last two decades tends to principally address the limit––that is, to question the impossibility of representing the “essence” of “being Costa Rican.” This art’s purpose is to bring to light the unsalvageable empirical distance that lies between the transcendent ideal presented as “the true Costa Rican” and “the real Costa Rican.” As Alexander Jiménez (2002), among others, demonstrates in his book El imposible país de los filósofos, the invention of the “national being” has taken place as a “metaphysical ethnic nationalism.” According to this idea, the inhabitants of this “tropical Arcadia” are modest and humble country people with Caucasian features and are thus carriers of a rationality superior to that of their Central American peers and neighbors, something made apparent by their pacifist and democratic nature. It is precisely the emerging “post-nationalist art” that intends to question this idealized image and thus comes closer to representing the “real Costa Rican” and its various manifestations. It thus calls into question “the ideal one” for the benefit of “the empirical multiple.” This precipitates an erosion of the internal limit as well as a blurring of the border between the Costa Rican and the Central American.

As mentioned before, this short text intends to present a preliminary interpretation of an artwork that I would like to characterize as an example that stands out in “post-nationalist” art from Costa Rica: the performance First Woman on the Moon by Elia Arce, a diasporic artist of Costa Rican origin who lived and worked in the United States for over two decades. For my interpretation, I use Debra Winsky Production & Nomadhouse’s visual recording of a version of the work presented in Havana, Cuba during Mayo Teatral, which took place on May 15th and 16th, 2004 at the Bertolt Brecht Theater.

My interpretation is inspired by Judith Butler’s (2002) reflections in Bodies That Matter. Like her, I believe that the “ground zero of the corporeal” does not exist: the body is always a culturally marked body. Bodies, however, are not only “gendered,” but also “nationalized.” This nationalization implies a disciplinary regulation of the body through the inscription of geopolitical cultural norms upon it. Just as there is a viable way of being a “female” subject, there is also a viable way of being a “national” subject. Like gender, nationality configures a “corporeal style” and a performative act, a norm and a “dramatic and contingent construction of meaning” (Butler 2002, 271). One could say that all of us, like the king, have (at least) two bodies: our personal body (individual, more an ideal type than anything else) and our political body (the incarnation of the body of the nation or, even better, the incarnation of the nation in our body). Thus, we feel compelled not only to create an “individual” style, but also to permanently enact the norm that is imposed on us since infancy: as Costa Ricans, Mexicans, or Germans, we talk, walk, gesture, follow proxemic patterns, etc. Our body operates as both an indicator of our national belonging and of the corporeal norm that it imposes upon us.

Performance Art as Deconstruction of the Body of the Nation

In First Woman on the Moon, Arce stages a very intimate autobiographical reflection on her personal identity as a Costa Rican who has immigrated to the United States. As is well known, migratory experience frequently fulfills a phenomenological function of “epoché” – that is, of estrangement, questioning, or suspension of the certainties of daily life in the place of origin. This has to do not only with a displacement in space, but also, with a cultural decentering in which everything we have experienced as “normal” or “natural” becomes relative and ultimately strange. This uprooting, the overwhelming presence of the “other,” the daily weight of the other’s “gaze,” and most of all, the strength of the latter’s classifying and normalizing interpellations destabilize us, forcing us to rethink, rebuild, rework ourselves as corporealized subjects in order to find a place for ourselves on a new stage. In this circumstance, the best we can hope for is relative success.

First Woman on the Moon is a piece of great complexity, both conceptually and formally, which is why I will limit myself to an exploratory and preliminary analysis of the manner in which Arce, as part of the Costa Rican diaspora, represents her relationship to her original national identity. My working hypothesis is that everything this performance piece presents as a personal, intimate reflection about Arce’s own identity is—inevitably, given the “duplicated” nature of the personal and the national body—a scathing critique of Costa Rican national identity. The performance is also, however, a message of hope regarding a female body’s creative potency, liberated from patriarchal and nationalist subjection. Thus, I will show how this performance problematizes both the border and the limit of national identity, an identity sustained by gender hierarchies in patriarchal societies.

Act One: The Bucolic Imaginary

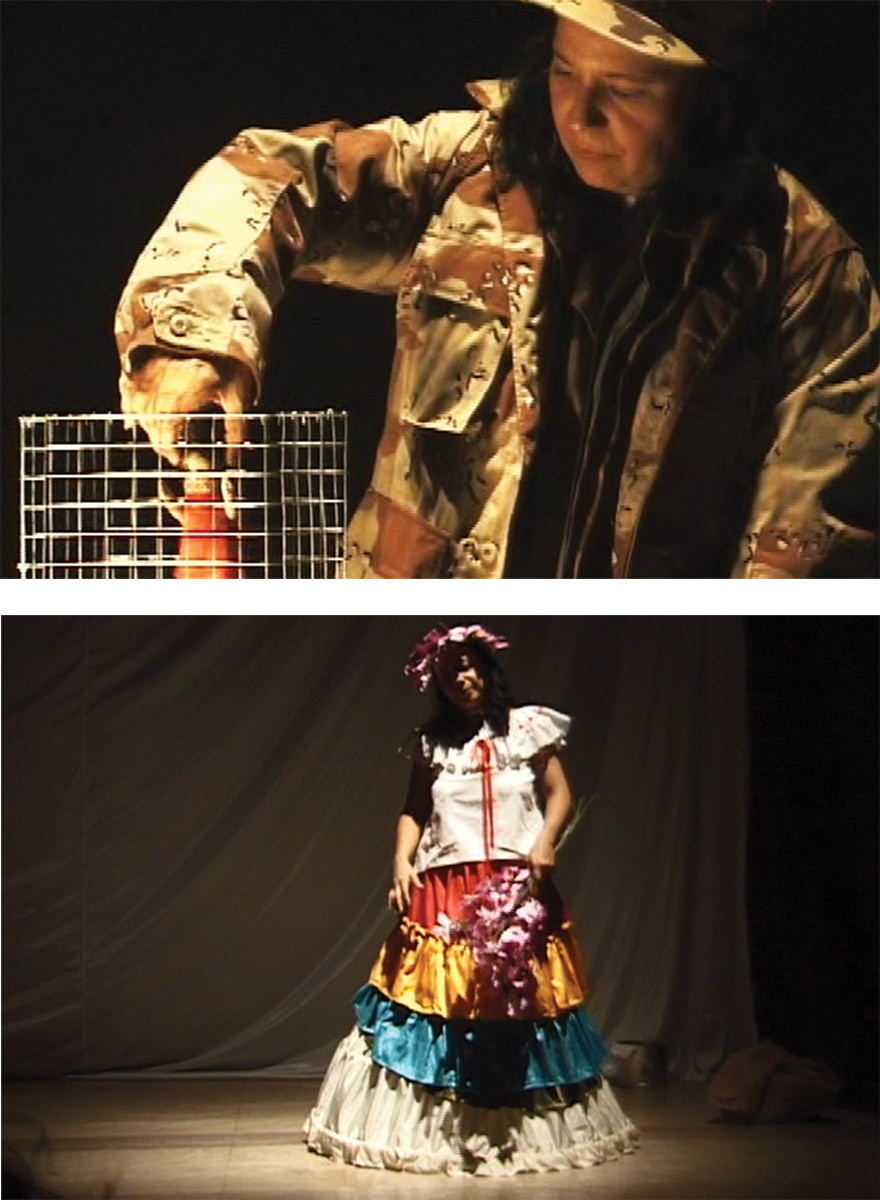

Arce begins with an interpretation of a “typical” Costa Rican dance, which features an “archetypal” representation of the “Costa Rican country girl.” The latter has been constructed through national folklore, the traditional dress from Guanacaste region, and the song of the Guaria morada. The attire consists of a white blouse, a long bell-bottomed skirt with colorful stripes, and a flower crown; the song is an elegiac tune dedicated to the Costa Rican national flower, the wild orchid. Taken together, these elements symbolize the ideal image of the Costa Rican country girl, which lies at the core of the folkloric corporeal norm taught to children such they may perform it during civic events taking place under the schools’ purview. As part of their civic education, all Costa Rican children must learn to dance the Punto guanacasteco and to sing the Guaria morada.

Thus, when a Costa Rican feels compelled to demonstrate what is “truly” Costa Rican, he or she will perform these pieces from the folkloric repertoire. This repertoire, as a whole, is a staging of “the natural humility and modesty of the Costa Rican peasant” ––values also canonized by the lyrics of the National Anthem, composed by José María Zeledón in 1902 (cf. Amoretti, 1987). It is precisely this demand for representations of these bucolic virtues––considered constitutive of the national identity––that encourages the adoption of a corporeal language. This language evokes––in all those who feel compelled to enact that cultural norm––a sort of childish ingenuity, not exempt from naughtiness, but absent of malice.[7] Following the performative theory proposed by Butler, we could say that it is precisely the production of “viable” national subjects––in this case, Costa Ricans––that occurs through this corporeal norm, enacted in a repeated and “natural” manner.

In Arce’s performatic representation of this corporeal norm, there is a process of distancing or “disidentification” from the nationalist interpellation, for her representation of the “civic act” is caricaturesque, carnivalesque, and bajtinian in nature. This parodic character emerges through the over-enactment of the infantile features that underlie the call of this bucolic imaginary. This over-enactment becomes evident not only through gestures, but also through the projection of the voice and the traditional dress—with the tight-fitting white blouse bursting at the seams as a vivid metaphor for the Real exceeding the Symbolic. Arce mentions that the attire she wears was made for her when she was eight years old, an age considered particularly important for primary socialization. This is the age at which the individual and their body are “marked” for the rest of one’s life. It is not a coincidence that it is precisely at this age that the first communion takes place in Catholic families. With this gesture, Arce seems to point out the “regressive” character implied by the representation of the national, the staging of the canonized country girl identity. She emphasizes––in her speech as much as in the act of building a fence with flowers she holds in her hands––the fundamental sentiment of being a private proprietor, the need to be “the owner of something,” of having something to call “mine.”

Assuming this identity and distancing herself from it through parody is an act motivated by an encounter with another character “from the outside.” She narrates an encounter with an elderly U.S.-American man who approaches her at a food stand in a Los Angeles market and asks if he can sit with her. After a period without communication, during which she––in a very Costa Rican manner––wants to say “no” but never does, only emitting a murmur (“mmmjú”) that the man interprets as a “yes,” she discovers that the elderly man is a retired military man who was once married to a Costa Rican woman. When the man mentions that his wife died not long ago, she snaps out of her silence, telling him “I’m Costa Rican, too!” Immediately after, the elderly man begins to sing La guaria morada in a gringo accent, and she joins in, creating a sort of national communion between them. This feeling is reinforced by the nationalist set design showing an image of the Irazú volcano––one of Costa Rica’s iconic national landscapes––projected in the background

The scene finishes when the encounter with this other, whose look constitutes her once again as “Costa Rican,” ends—a moment in which she goes beyond parody and radicalizes her act of national disidentification by slowly but decidedly removing the traditional attire imprisoning her. The blouse is so tight that it looks more like a straitjacket than an ontological cocoon provided by her “Costa Rican” identity. The process of undressing in this performance piece can be interpreted as an act of subject-formation, in other words, a political act that implies the transformation of a representational character into a subject making its own history. Through this ethico-political act that she uses to traverse the ghost of the nationalist imaginary, Arce represents her own “identicide”: her detachment from this socially-assigned identity that she has experienced as an oppressive cage.[8]

Act Two: The Staging of the Real / Abject

The next step in Arce’s performance is to demonstrate even more clearly the limits of being Costa Rican. For her, it is not only about making the external differences visible (the border between the “Costa Rican” and the “foreign”), but also about the internal inconsistencies that cut across them. Thus, Arce seeks to reveal not only the limit of national unification, but also its precariousness. In this way, she directly profanes the especially sensitive discourse of Costa Rican (supposed) pacifism.

The second scene begins with the song “Playa Girón,” a tune by Silvio Rodríguez that does not evoke anything Costa Rican, but rather the Cuban Revolution. This musical accompaniment defines the context in which the second act takes place: the Cold War, specifically its relation to Costa Rican “pacifism.” Arce represents the “dark side” of Costa Rican identity, everything that calls into question the advertised local pacifism and brings to light the country’s covert militarization during this period. In a ceremonial manner, Arce puts on a series of military jackets (“chaqueta army,” as they are usually called in Costa Rica), while she narrates her views on the Costa Rican police and their transformation over time.

Simulating a contemptuous tone that Costa Ricans usually adopt when talking about something that they do not like or that makes them uncomfortable, Arce begins by talking about how policemen always wore dark olive-green uniforms when she was a child. They were peasants without education, unarmed, pitiful, for whom people on the streets had little respect and who were often mocked. Then, she enacts the metamorphosis of their appearance, a process aligned with—even if only as a distant echo—the different military actions of the U.S. Army abroad. First, the uniform turns into a jungle camouflage, signaling the moment the U.S. intervenes in Central America. A combined camouflage (jungle/desert) follows during the “Operation Desert Storm,” and finally the uniform becomes full desert camouflage just as the U.S. invades Afghanistan. Finally, it becomes a uniform similar to that of the riot police (the most feared one in the United States, according to Arce’s account) in the context of the so-called “war on terror.”

The artist points out that these small but significant details regarding a change of apparel usually go unnoticed by common people because—and here she exaggerates her nationalist intonation with sarcastic purpose— “as you know, in Costa Rica we don’t have an army, only a police force.” Next, Arce adopts child-like gestures and begins a school-like recitation, but this time, it is completely distanced from that innocence characteristic of representations of the country girl identity, for it is saturated with violence:

As she recites this, Arce begins to dress a little doll in red, which she then––as if it were nothing but a childish game––forces to undergo waterboarding and locks up in a cage, no doubt alluding to the political repression against “red” women. Here, she stages, from a child’s perspective, the experience of the Cold War and the repression directed at those labeled “communists” by police and military forces in various Latin American countries during the dictatorships and civil wars of the 1970s and 1980s.

Immediately thereafter, Arce again begins to remove her clothes, to un(ad)dress. In this manner, she stages a new disidentification, this time with the violence disavowed by Costa Rican national identity. This violence, as one can imagine, is usually obliterated in nationalist discourses celebrating pacifism as one of the “metaphysical ethnic” features of Costa Rican national identity, as Alexander Jiménez describes in the aforementioned book. As the stage goes dark, the speakers broadcast music that recalls Yoruba songs of Cuban origin.

Act Three: The “Invisibilized Internal Other”

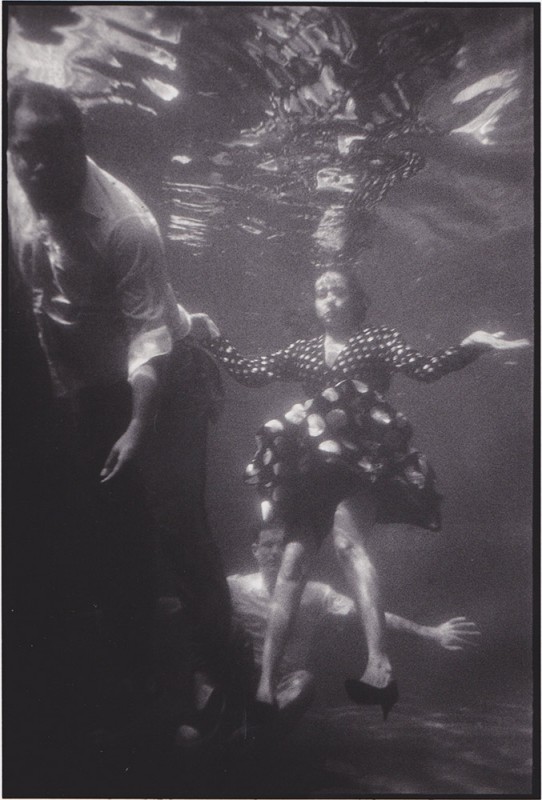

The third act “occurs” in the foreclosed territory of Costa Rican national identity, the Caribbean coast.[9] Arce, who appears on stage naked, covers her head with a print scarf, puts on sunglasses, and paints her body black as a way of identifying with the people of Limón (limonense). With deep irony and employing terms that, from a hegemonic position, are utilized to stigmatize Limón and its people – terms that we use in quotation marks here – she describes the manner in which she has imagined and lived her relationship with the country’s the Caribbean coast. She narrates that the jungle is a dark, dense, and humid place, a marginal place where all rules are broken, where there is no word for sin. She tells of meeting a group of foreign and Costa Rican women, who spoke of the “libertine” sexual relationships they had established in that “land of sin,” which has been transformed by rebel women from various places into a paradise where they could take refuge, ostentatiously living out their sexuality. Arce intersperses a calipso song––“typical” music in Limón––in her narration: “give me some of your rice and beans,” lyrics that, in this context, acquire a sexual connotation.

Afterwards, she confides that she fell in love for the first time in Limón, where she had decided to live and possibly start a family. For Arce, this manner of “becoming black” and taking root in the “land of sin” would consequently mean a disidentification with the Costa Rican “ideal self” from the Central Valley, and an identification with the Caribbean coast, a process that also reveals a hope for happiness and fulfillment. This metamorphosis implies a certain transgression of the symbolic order and of the imaginary that stitches it together. It serves to distinguish, in the internal margins of the nation, an “other” zone, one that appears liberated from the stigma of sinful perdition and that emerges as a place promising happiness once the phantom of “primitive,” “savage,” and “sinful” abjection is encountered.

This promise of happiness, however, turns out to be ephemeral, for it is more illusion than reality. The dream does not come true because the Caribbean is threatened by destruction, a ransacking by an oil company. Here, the threat to paradise arises not from war, but from extractivist voracity. This phenomenon is also the theme of Esteban Ramírez’s film Caribe, the most expensive Costa Rican film ever made. Experts say that once oil exploration and exploitation begin, the entire coast will be contaminated and destroyed, including the most remote zones (like Playa Manzanillo) where, until recently, it was not even possible to arrive by land in a motorized vehicle. The voracity of the transnational corporations (the “Chicago oil company”) thus means the end of paradise and, with it, the impossibility of finding redemption in the “dark side” of our own country. The result is expulsion into the “American dream.”

Here, Arce alludes to two “referents” of Costa Rican national identity: the “black” side, denied up until recently and still today only timidly incorporated; and the repeatedly publicized ecological vocation of Costa Ricans. Arce’s staging can be understood as a critique intended to signal that the promise of the Caribbean paradise, with all the sensuality of its only recently acknowledged blackness, is threatened by the voracity of transnational corporations and the complacency of Costa Rican authorities. Here, Arce articulates the demands of Afro-Costaricans as well as an accusation of ecocide. In this way, she assumes a position similar to that sustained by author Ana Cristina Rossi (see La loca de Gandoca [199]), Limón Blues (2002), and Limón Reggae [2007]) and novelist Tatiana Lobo (see Asalto al Paraíso [1992], and Calipso [1996], as well as her historical essays).

Act Four: Immigrant, Go Home

The next act begins when Arce cleans her face and puts on red lipstick. From a small suitcase, she removes a red scarf that she wraps around her neck, as well as a few cameras that she uses to simulate a tourist’s photo shoot. Immediately following, she puts on a pair of “Playboy”-like bunny ears, accompanied by an idiotic gesture that suggests her transformation into a sexual object. She has arrived in the United States in search of the American dream. She is dazzled by the lights of the big city, the very lights that blind those recently arrived from the periphery and that keep them from seeing the dark side of the First World.

During this act, Arce narrates her experiences in this country of the North. She begins with her experience of uprooting as she observes that, since she has arrived there, not a year has passed in which she has not wished to return to Costa Rica. She also narrates her desperate financial situation, which takes her to a community dining room where – after five years of being a vegetarian – she succumbs from hunger to an impressive five pounds of pork, thus discovering that she has not been cured of her Costa Rican “cultural culinary heritage.”

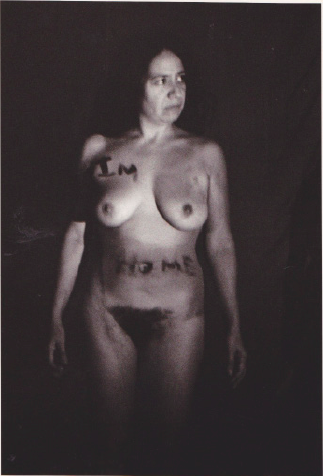

This traumatic event leads her, unconsciously (“where my body may take me”), to the Los Angeles airport (images of a freeway are projected in the background), where she experiences another identitarian shock. At the counter of a Central American airline, she stands in front of a gigantic mirror made out of smaller mirrors, in which she sees her image shattered, her identity dismembered. Despite the profound impact of this encounter with her own fragmented, irreconcilable identity, she confesses that she was unable to cry. In the midst of a silence that evokes loneliness and abandonment, the artist undresses and writes “imigrant [sic], go home” on her torso with blue pigment.

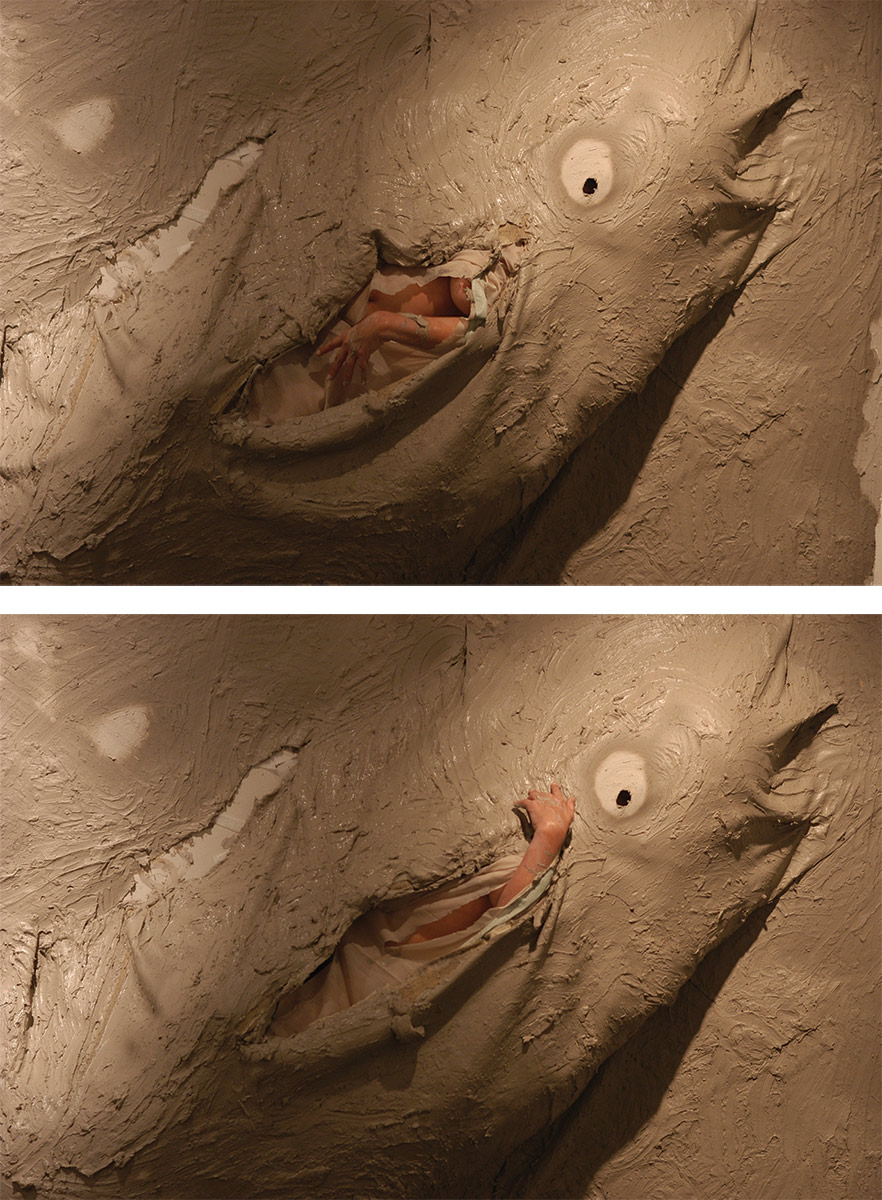

In the next sequence, Arce takes a clump of clay into her hands and patiently begins to mold the body of a baby. She narrates that “her last abortion” was performed at a community clinic by a doctor who was later accused of murder. She notes that abortion is illegal in Costa Rica and that if you are poor in the United States, after giving birth you are made to feel like “an illegal.” She rocks the baby molded from the clay and sings “Happy Birthday,” before letting it fall and crash on the floor.

Act Five: The War, The Mourning

The next scene begins with a narration about the noises and tremors generated by the U.S. Army battle drills in front of her house, near Highway 62, located on Native American land that at some point was offered as space for a national park. After this preamble, Arce narrates her encounter with a Cherokee friend, who had been a member of the Special Forces stationed in Bluefields during the conflict in Nicaragua of the 1980s. He had served as a military instructor for indigenous Miskitos who had enlisted in the Contra army. Facing the discovery that both of them had lost friends in that war, the Cherokee man––who also turns out to be a shaman healer––gives her the feather of an injured eagle, “from one injured warrior to another.” She takes the feather and exclaims, “May no Indian fight another Indian ever again.”

Then, she initiates a kind of mortuary ritual. She removes the “red” doll from the cage and undresses it (that is, she strips away the stigma that brands her as “red”). She recites, “Hail Caesar, we who are about to die salute you,” as if it were an expiatory ritual. She lays the doll’s “cadaver” on the eagle feather, which is placed on a piece of cloth cut from a military uniform. She wraps the body, creating a shroud. She sings a Cherokee song and lights a censer, with which she smokes the body as a ritualized form of purification. The dead have been honored, mourning has been completed.

Act Six: A New Origin

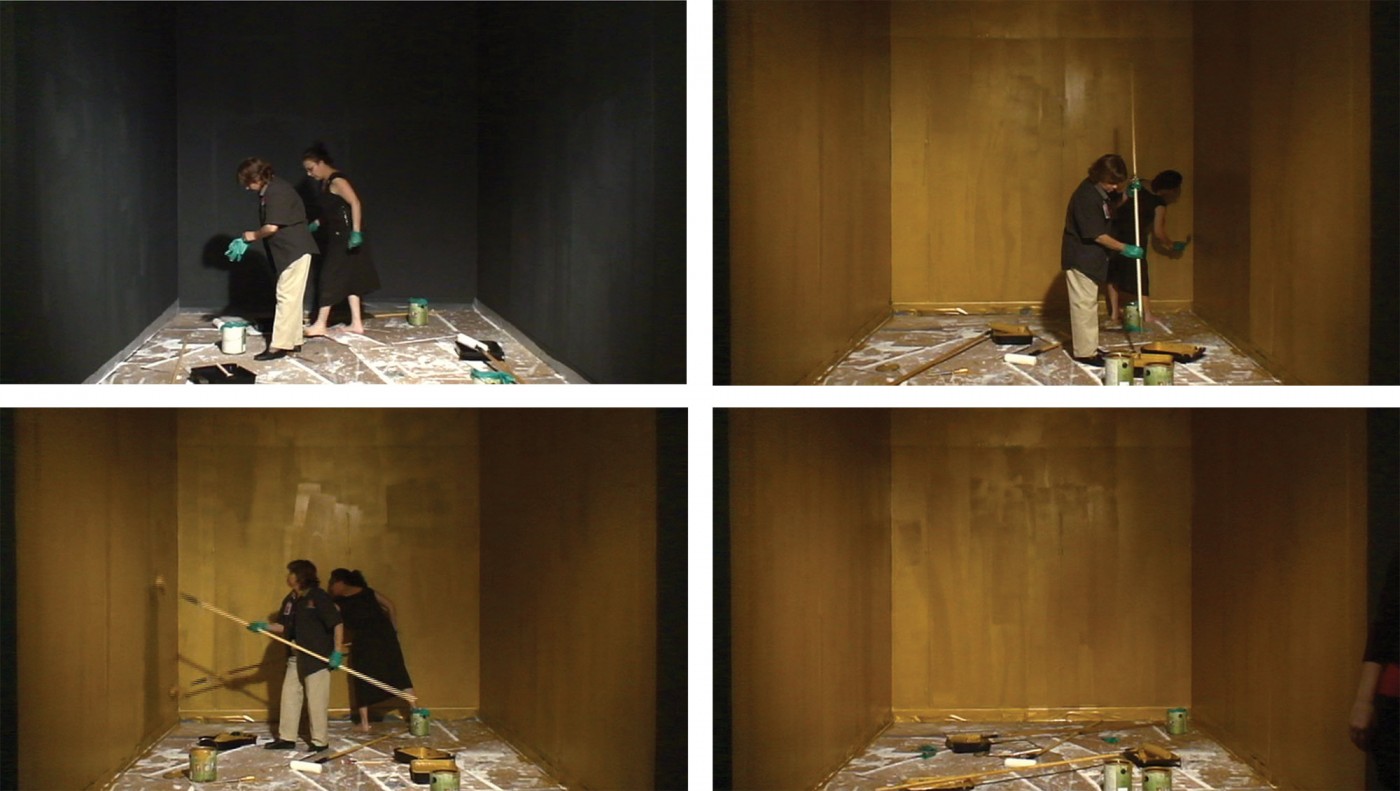

Arce zealously cleans the floor with a rag that she soaks inside a metal bucket, delivering a speech about order and cleanliness as divine mandates learned during childhood in a “typical” Costa Rican home: “Stuff, we have to control the stuff…a place for everything and everything in its place.”

She makes a discursive break and begins to narrate how in the town where she lives, close to Salt Lake City—a place where bomb tests are regularly conducted—they are building the “largest garbage dump in the world.” She recites, “When the earth trembles, the bottom of the ocean rages,” after which she sings the Ave Maria. While singing, she removes the message she had written on her torso, but she leaves behind the letters “MI” (from “IMIGRANT [sic]”) and paints “HOME” on her abdomen. In the background, the image of a dried-out land is projected, the earth entirely cracked, as if devastated by drought.

Against this desolate background, Arce bows reverentially and picks up the clay she used to mold the baby that she later dropped. With the paste, she makes small piles that she lays on the floor to serve as a foundation to support the flower bouquets that she had left on the floor at the beginning of her piece. Thus, the fruit of her womb that had lain dead on the floor becomes fertile soil that nurtures a garden of wild orchids. The precarious garden not only symbolizes the rebirth of life against the background of destruction, but also evokes the rebirth of the Costa Rican nation.

The lights are turned off, and immediately thereafter, three glass containers of different sizes are illuminated, accompanied by three sieves of equal size. Arce pours the liquid she used to clean the floor into the containers and narrates that the bottom of the ocean has no water left. Afterwards, she ritually drinks the cloudy water from the smallest container and picks up a sack of soil that she uses to form a mound at her feet, as if she were “sowing” herself. Other people step onto the scene to irrigate the mound at her feet with the water deposited in the containers, while she, with a vital breath, spreads the rest of the wet soil held in her hands onto the stage.

The stage becomes dark again. When a spotlight is turned on, we see Arce sitting on a small wooden stool, and on her back, which faces the audience, is the projected image of a green plant drawn freehand with a marker. It begins to grow. The background shows, in sequence, the planet Earth, cosmic archeological images, and the Milky Way, as well as Arce’s naked body on a circle of soil. She holds a flashlight in her hand, an illuminating light in the universe, while the speakers emit the sound of bubbling water and the sound of life that multiplies and grows until both become deafening.

Prolonged applause.

Tentative conclusions

The performance by Elia Arce analyzed here is an example that stands out in the battle for the liberation of the female body from oppressive cultural conditioning and the liberation of its creative and redemptive potency. First Woman on the moon is an allegorical representation of the female body’s liberation from the identitarian shackles imposed upon it. Arce stages a dramatic process in which her body gradually liberates itself from the various cultural straight jackets that attempt to mold and limit it.

She begins with a deconstruction of the “positive” national identity configured as the “Costa Rican country girl,” which perpetuates the romantic exoticism of the “repose to the [imperial] warrior”. She continues with a visibilization and deconstruction of the negative “red” identity stigma imposed by state violence framed by the Cold War, even in a country that declared itself pacifist. She then proceeds with the deconstruction of her own illusion that generated identification with the “internal other” in a land of sexual liberation threatened by irrational economic exploitation.

She then narrates the drama of suffering––stigma, hunger, and sexual violence––that immigrants carry from the South to the North. This anguish grows because the narrated history of uprooting is added to the drama of the destruction of the planet and its ecosystems––resulting from the unfolding of instrumental rationality itself, which, as Adorno and Horkheimer asserted in Dialectic of Enlightenment, is the warlike and industrial irrationality exercised on nature and humanity.

But after the destruction comes the rebirth: the first step is the encounter with her Cherokee friend, a sort of emblem for Arce of the “South” in the “North.” His shamanic knowledge allows for both mourning and a rebirth of the hope for a return to “my home.” This Native shamanic energy is a catalyst for the potency of the liberated feminine, for the creative potency of the feminine: the fruit of her womb––a symbol of violence and death––turns into fertile soil from which life blossoms. Arce represents a primordial woman who plays a double role—that of a life-giving goddess (the vital breath), and that of the living matter upon which this creative force is exercised, Mother Earth.

Thus, First Woman on the Moon operates as a liberation allegory of the creative potencies imprisoned within subaltern bodies, as well as of subaltern feminine subjectivity as a condition for rebirth. The elaborate staging of this monologue narrates the dramatic liberation from the subalternizing conditions of a generic, national, immigrant, and indigenous identity, which in its successive contact with power and the abject, gradually finds the path to a full and generative subjectivity once again. It is a message of hope, but also of suffering: to find life again, it is necessary to go through a long and painful process of both resistance to power and identification with the abject; to paraphrase the tango “Cuesta abajo” by Carlos Gardel: to be reborn, we must live through the pain of no longer being, we must become “nothing.”

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 2011. Desnudez. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Amoretti, María. 1987. Debajo del canto. San José: UCR

Butler, Judith. 2002. Cuerpos que importan. Sobre los límites materiales y discursivos del “sexo.” Barcelona: Paidós.

Foucault, Michel. 1992. Vigilar y Castigar. México: Siglo XXI.

Jiménez, Alexander. 2002. El imposible país de los filósofos. El discurso filosófico y la invención de Costa Rica. San José: Perro Azul.

Kauffman, Linda S. 2000. Malas y perversos. Fantasías en la cultura y el arte contemporáneos. Madrid: Cátedra.

Kristeva, Julia. 1988. Poderes de la perversión. México: Siglo XXI.

Mandel Katz, Claudia. 2006. Un mapa del cuerpo femenino y su deconstrucción en las artes visuales contemporáneas. San José de Costa Rica: Universidad de Costa Rica.

Perniola, Mario. 2002. El arte y su sombra. Madrid: Cátedra.

Ramírez, Juan Antonio. 2003. Corpus solus. Para un mapa del cuerpo en el arte contemporáneo. Barcelona: Siruela.

Silverman, Kaja. 2009. El umbral del mundo visible. Madrid: Akal.

Schneider, Laurie. 1996. Arte y psicoanálisis. Madrid: Cátedra.

Villena, Sergio. 2010. “Regina Galindo: El arte de arañar el caos del mundo. El performance como acto de resistencia”. En Revista Centroamericana de Ciencias Sociales, vol. VII, nº 1.

Villena, Sergio 2015. El perro está más vivo que nunca. Arte, infamia y contracultura en la aldea global. San José: Germinal.

Zavaleta, Eugenia. 2003. Haciendo patria con el paisaje costarricense: la consolidación de un arte nacional en la década de 1930. San José: Ed. de la Univ. de Costa Rica.

Žižek, Slavoj. 1998. Porque no saben lo que hacen. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

The artist Edgan León, who is from the province of Limón, has dealt with this issue in an acrylic on canvas by the name of Geografía sin limón ni sal (110 cm x 110 cm, 2011), on which he “drew” a map of Costa Rica using only material structures, with the part corresponding to Limón missing. The title, of course, is a reference to the usual absence of this province in the imaginary geography of the official nation, which focuses on the Valle Central, and it also alludes to the loss of Limón “flavor” implied by this mutilated representation of Costa Rica.

This mechanism of “disidentification“ has been used as the vicissitude or the unchaining of the action in several novels by the Costa Rican writer Fernando Contreras: in the novel Los Peor, Jerónimo loses his ID card; in Única mirando al mar, the main character commits “identicide” by throwing himself into the garbage; in Cierto azul, Arturo, the young protagonist, runs away from his paternal house (a house that appears, in nationalist literature, as Arturo, the young protagonist, runs away from his paternal house (a house that appears, in nationalist literature, as the symbol of harmony that nests under the protecting mantle of the patriarch)

This canonic representation of the Costa Rican emerges towards the end of the 19th century and takes shape in the National Anthem, as well as the national literature, especially in Concherías, a foundational work written by Aquileo Echeverría.

On the concept of heteropathic and excorporate identification, see K. Silverman, The Threshold of the Visible World (2009).

Here, I follow the distinction that Zizek makes between “limit” and “border” with respect to national identifications: “National identification is an exemplary case of how an external border is reflected into an internal limit. Of course, the first step toward the identity of the nation is defined through differences from other nations, via an external border: if I identify myself as an Englishman, I distinguish myself from the French, Germans, Scots, Irish, and so on. However, in the next stage, the question is raised of who among the English are ‘the real English,’ the paradigm of Englishness; who are the Englishmen who correspond in full to the notion of English.” (1998: 151)

It is no coincidence that among the painters “recovered” as objects of worship in contemporary times, we find precisely those who at the time defied the Christian canon or the neoclassic canon: for example, Hieronymus Bosch and Brueghel “the Elder.”

Agamben makes a very interesting reflection on “innocent” nudity before and after “the fall,” whose main characters are Adam and Eve (cf. Agamben, 2011).

The classic Greek canon – attributed to Polykleitos and reconstructed by Winckelmann – establishes a strict conjunction of proportion and composition rules for the representation of the gods’ and heroes’ beauty in their age of virility. Similar to this, though with the opposed value sign in relation to nudity, was the canon of Christian painting, dominant in Latin America until the end of the 19th century, when the change in sensibility promoted by liberalism brought tastes closer to neoclassic patterns (at least among the elites). As a result, republican architecture remained branded by the profusion of allegorical frescos, on which nymphs and Venus were often painted with the faces of the current governing politicians’ daughters.

Norbert Elías demonstrates in La sociedad cortesana and El proceso de civilización how the codification of gestures and the control of posture, among other “table manners,” can also be oppressive mechanisms, even for the upper classes. For Foucault, however, the rationalizing and disciplining process responds to a will for domination and power (negative bias), while for Elías, this is the path on which civilization advances (positive character).