Elia Arce is a complete artist. She has shown, among many other virtues, the capacity to consolidate diverse forms of artistic work with an admirable independence. An academically trained actor, she is also a performance artist and a video producer. This multiplicity of skills is, perhaps, a projection of the vicissitudes of her own precarious stability, her permanent disquietude, stemming from the fact that she has spent her life moving from one place to another. Her montage First Woman On The Moon (2001) proposes an exploration of a kind of nomadism that leads her to revisit her mutating identity, beginning at Joshua Tree in the California desert, where she lived at the moment of the work’s creation and where she, for the sake of consistency, eventually moved away from. This piece takes her across borders, on a journey in which she examines the history of Central America and its militarization by the United States.

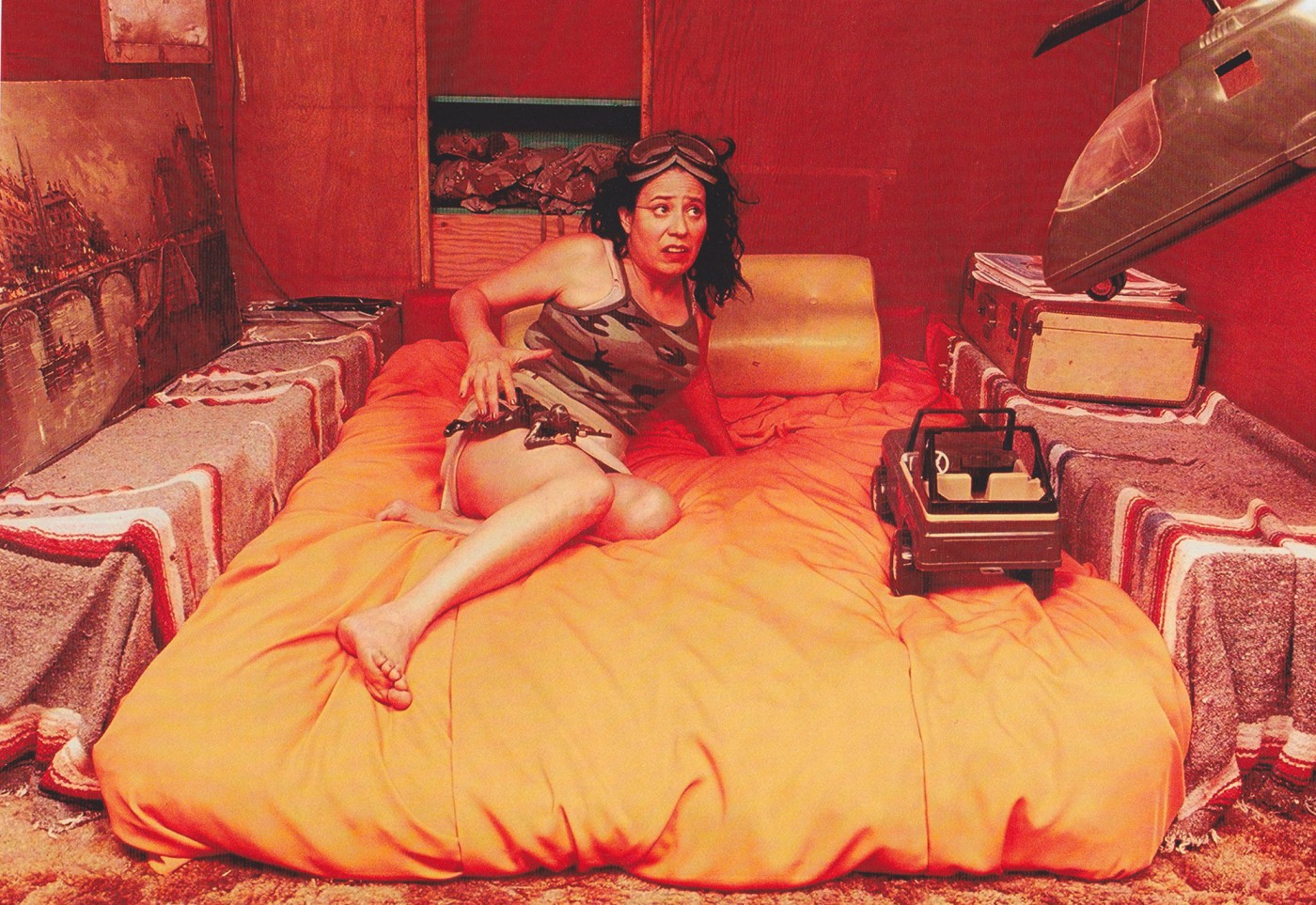

On stage, Elia combines the presence of her body, naked for a good portion of the time, with the conceptual disposition of the elements inside the space—a suitcase, a camera––eloquent signs of the journey––plus a plastic basket, a cage, a crystal glass, water, soil, flowers, and clothes. To this, she adds a projection of images that move from incredibly green rural landscapes from her native country, to Los Angeles highways and intersections, to arid deserts, to the lunar landscape.

Elia turns her own body into a map of her migratory existence, a kind of political geography of her historical memory. At the beginning of the piece she proclaims, “from the moment I left Costa Rica, I have lived in twenty-seven places.” Over the course of the montage, she becomes a small-town girl with flower garlands on her head, and later a member of the Costa Rican police force. As she moves from one camouflage uniform to the next––one covert or overt North American intervention to the next––the figure becomes a U.S. Marine with deadly capacities. Then, she is the lost woman in a strange land, the one who loses what was going to be her first child due to poor sanitary conditions. With her hands, she transforms clay into that lost child, physically representing her amputated motherhood. She witnesses military training maneuvers in the desert, which pose health risks and which may be related to some new imperial military invasion. The shared experience involves us in the ritual of a journey, physical and interior, that travels through her personal history.

As she repeatedly undresses, Elia rebels against the sexually charged gaze that Jean Franco (1996) denounced when she stated that “the woman’s body continues to be defined according to a Catholic morality, in the midst of a consumer society characterized by the incitation of desire.” It has always amazed me how direct a performance piece can be. The uninhibited manner of adopting nudity during an exchange with the audience unfolds as a simple relationship––curiously and paradoxically––in an environment that is in no way extraordinary and which reaches a touching and intimate human

dimension.

The artist is also the fearful woman who is facing something new, something different, the Other. And she is painfully stricken by the dehumanizing evidence of the interpersonal relationships of the world we live in. I quote the text from First Woman on the Moon:

“I’m afraid of you,” I told my new friend, the healer, a Native American man who has been a soldier for the U.S. Special Forces. His mission had been to train Miskito Natives in Bluefields, Nicaragua, to fight against us. “Some of my friends died there,” I said to him. “Some of my friends died there, too,” he said to me. He took out an eagle feather and put it in my hands. “The feather of an injured eagle for an injured warrior. From one injured warrior to another, to not having an Indian fight another Indian ever again!”

On her torso, Elia imprints signs that have accompanied her on her life path and as an artist: an offensive sign that reads “immigrant, go home,” which she later erases, leaving only the indelible end of the text, “my home.” From her non-place, which speaks of uprooting and an identity in

permanent conflict, emerges a place of lunar, feminine affection, based on memory as one of the most precious tools of survival, as well as of cultural and human learning, both practical and emotional. Therefore, First woman on the moon is also a physical and sensorial exploration of vital, fictional, imaginary, and sensory spaces.

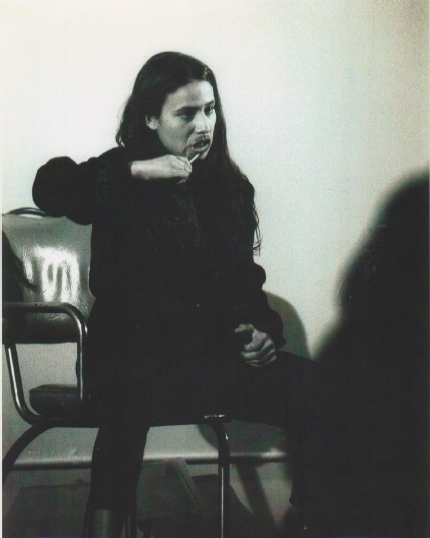

Working from a deliberately experimental perspective that mixes experience from theater with performance art, Elia does not offer a psychologically outlined character; rather, she presents herself with her memories and obsessions, while also presenting similar and familiar situations from others close to her. Her acting has a provisional impression and her gestures and movements have a somewhat distinct quality. Their precision is not always the most important feature, but they bear an unequivocal stamp of authenticity.

The efficacy of her discourse fascinated me when I first saw her perform at the International Festival for Latin American Theater of Los Angeles in 2002. I fulfilled a dream of mine when I included her in the program at the Latin American and Caribbean Theater Season Mayo Teatral in 2004, which I curated from Casa de las Américas and was able to enjoy at the Bertolt Brecht Cultural Center in Havana, watching the Cuban audience interacting with Elia. My profession however, would bring me another special moment related to her work in October 2004, when I was on my way to the Ibero-American Theater Festival in Cádiz to give a talk on female discourse in Latin American theater at the Ayuntamiento de Peligros near Granada.

En route to the forum in the company of the hosts, I thought I would be speaking to a group of academics and local professors. To my surprise, I arrived to find close to forty elderly women waiting for me, accompanied by half a dozen elderly men. At first—ah, the prejudices we carry around!—I was overcome by the fear that the topics or video images I was going to show would scandalize or bore them. I put all of my energy into making my talk appealing and to making the illustrations familiar to the audience. For over an hour, they remained attentive and interested. To my surprise, when I invited them to comment or ask questions upon concluding my presentation, one of the oldest women––I would guess she was in her 80s––sitting in the middle of the first row, without raising her hand, began to tell us about the part of First Woman on the Moon in which Elia Arce recreates her miscarriage with a clay fetus. It reminded the woman of a time in her early youth when she worked on a field harvesting olive trees with a friend. She recalled how one day, her friend asked her to accompany her behind some trees nearby to urinate. “Back then,” she added, “we called it peeing.”” They asked permission from the foreman, who was a very upright man, and when her friend crouched to the ground, a stream of blood flowed out from between her legs. She grew very scared and lent her own underwear so that her friend, who was having a miscarriage, could cover herself. She explained to the foreman what was happening and managed to get permission for the pair to leave. She then took her friend to her own house, so that her mother could prepare a glass of hot milk for the girl, for her family did not and could not know she was pregnant.

The tale was so vivid that the old woman’s voice came out like a torrent,the dictation of a memory activated by the impact and force of the dramatic image. She recounted something that had occurred over sixty years ago and which, as she told us, she had never spoken about before. This led me to believe that this single experience had made my conference a valuable act, and reaffirmed the powerful energy and talent of a Costa Rican, Latin American, and universal artist.

*The ideas presented in this paper first appeared in “Estéticas y políticas del espacio en Elia Arce y Ana Correa,” Affidamento, mujer y cultura, a. 2, n. 13, Mexico City, 2nd half of January 2010, pp. 5–6, and are part of a more extensive essay about female discourse in Latin American theater, currently in the process of revision.

References

Franco, Jean. 1996. “‘Desde los márgenes al centro’ tendencias recientes en la teoría feminista.” In Marcar diferencias, cruzar fronteras. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 1996.